How to Write -- The Content

Writing Begins with Research

Before you begin writing audio description of a work of art, you must gather information on the artist, the style or school of art, whether the artist has written or spoken about his or her work, what critics have written, and how the public has reacted. The point is that the verbal description should not be about your opinions. You must filter all the information you find and synthesize it into your audio description.

If you’re able to interview and record an artist, you can edit an audio clip into your verbal description. Even a recorded telephone conversation is usable. I have recorded short phone interviews with artists and included excerpts in the audio tour stops about their works. Artists have talked about their inspiration, their technique, or how they hope the viewer will react. I’ve even asked artists how they would describe their work to someone who cannot see it. Hearing the voice of the artist makes a compelling connection for listeners, both sighted and blind.

What to Say First ?

Whether you are writing a Classic, Audio Descriptive, or Inclusive tour, here's the best way to start. Imagine you are the listener and as quickly as you can, answer this question: "What is in front of me?" Ideally, the answer should be in the first sentence. Do not begin with a thirty second (or more) essay of introductory material like curatorial or historical background that leaves the listener standing and wondering "Why am I standing here?" You can weave the information into the stop later in the script.

For artworks, start simply and directly with basic information: the title of the work, the artist’s name, the medium, maybe the year it was done, maybe where it can be seen. The client you write for will determine what you include.

How would you judge the opening sentence in an audio description of this painting?

Early Sunday Morning is an oil painting on canvas by Edward Hopper in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Before you begin writing audio description of a work of art, you must gather information on the artist, the style or school of art, whether the artist has written or spoken about his or her work, what critics have written, and how the public has reacted. The point is that the verbal description should not be about your opinions. You must filter all the information you find and synthesize it into your audio description.

If you’re able to interview and record an artist, you can edit an audio clip into your verbal description. Even a recorded telephone conversation is usable. I have recorded short phone interviews with artists and included excerpts in the audio tour stops about their works. Artists have talked about their inspiration, their technique, or how they hope the viewer will react. I’ve even asked artists how they would describe their work to someone who cannot see it. Hearing the voice of the artist makes a compelling connection for listeners, both sighted and blind.

What to Say First ?

Whether you are writing a Classic, Audio Descriptive, or Inclusive tour, here's the best way to start. Imagine you are the listener and as quickly as you can, answer this question: "What is in front of me?" Ideally, the answer should be in the first sentence. Do not begin with a thirty second (or more) essay of introductory material like curatorial or historical background that leaves the listener standing and wondering "Why am I standing here?" You can weave the information into the stop later in the script.

For artworks, start simply and directly with basic information: the title of the work, the artist’s name, the medium, maybe the year it was done, maybe where it can be seen. The client you write for will determine what you include.

How would you judge the opening sentence in an audio description of this painting?

Early Sunday Morning is an oil painting on canvas by Edward Hopper in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Seems like efficient, succinct writing, direct and straightforward, no? It is, for a reader. But it contains four bits of important information that fly by the ear. Easy to read and reread. Not as easy to hear and retain. It’s better to deliver the facts individually, in sequence, starting with the most important facts.

The title of the painting is Early Sunday Morning. The artist is Edward Hopper.

It’s an oil painting on canvas. It’s in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Then Offer Dimensions

Your goal is to help visitors build an image in the mind. Dimensions can be a first step in incrementally building that image. For paintings and sculpture, give listeners the dimensions of the work. Be specific if you know the dimensions or tell listeners if you are approximating.

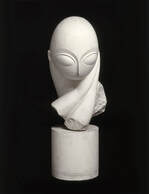

The sculpture is 18 inches tall. It stands upon a pedestal about 3 feet tall

The painting is a rectangle about 3 feet wide and 2 feet high.

To help convey dimensions, you can compare the size and dimensions of a work with a work to familiar objects visitors might know.

It's as big as a [car, a soccer ball, a fist].

The railing is waist high.

The body of the teapot has the shape of a pear standing on its end.

The bell tower's three sections look like three square boxes piled one atop another.

Then Give the Big Picture -- Don't Start with a Detail

It’s best to then quickly offer the overall impression of a work that most viewers have, the content as well as style, if appropriate. You're going to start with the general and then move to the specifics To continue using Hopper’s painting as an example:

It shows a block of three attached buildings, all two stories tall, with shops on the street level and apartments above them. The buildings extend horizontally across the painting from the left edge to the right edge.

Sometimes it is possible to be a bit more intriguing in your summary.

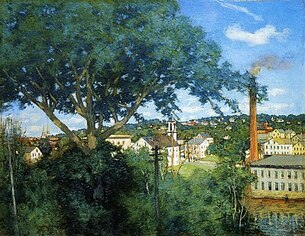

For the painting at right by J. Alden Weir titled The Factory Village, I wrote this introduction:

The essence of what you see in the painting is a factory and a village.

But what dominates the painting is instead nature.

Establish a Point of View

For a representational painting, describe the point of view the artist has given the viewer, who is now your listener. Are we seated across a table from the subject or are we across a field? Are we looking down on or up at the subject? Again using the Hopper painting:

You see the buildings as if you’re standing across the street from them.

For the Weir painting above, you might write:

The view is from a hill looking down into a New England village from a distance.

But the view is partially obstructed by a large tree on your left in the foreground, close to you.

Also, when you use phrases like “to the left” or “on the right,” explain whether you’re referring to your point of view as viewer of the painting, or the point of view of the subject in the painting.

For describing sculpture, it’s equally important to establish a point of view for the listener. Where are you standing as you describe? Facing its front? Or side? Looking up at it from its base? Explain if you are describing one point of view, or if you will describe it from various points around it.

As the audio description continues, remember that you are incrementally building up an image in the mind of the listener. Each line should add to that image in an order and in sequence. And you should first tell the listener what that order will be.

I will describe the sculpture starting with the crown on his head, moving down to his feet.

The painting is primarily made up of three horizontal sections. I will begin with the upper third of the painting.

Then Bring on the Details -- in Some Order

Plan the best sequence for describing the details. Sometimes it's best to start at the bottom and move up. Or vice versa.

Or maybe begin with the most prominent feature and move from that. The key is to follow a certain order, and whatever you decide, tell your listeners the plan to help them prepare to build their mental image. For example:

The painting is primarily made up three horizontal sections. I will begin with the upper third of the painting.

I will describe the facade of the building by beginning at the ground floor and moving up to the roofline.

As your audio description continues, remember that you are building an image in the listener's mind.

Direct the Listener’s Pose

Sometimes you can suggest that a listener use his or her body to feel a certain shape, or to understand the pose of a figure in a painting or sculpture.

The title of the painting is Early Sunday Morning. The artist is Edward Hopper.

It’s an oil painting on canvas. It’s in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Then Offer Dimensions

Your goal is to help visitors build an image in the mind. Dimensions can be a first step in incrementally building that image. For paintings and sculpture, give listeners the dimensions of the work. Be specific if you know the dimensions or tell listeners if you are approximating.

The sculpture is 18 inches tall. It stands upon a pedestal about 3 feet tall

The painting is a rectangle about 3 feet wide and 2 feet high.

To help convey dimensions, you can compare the size and dimensions of a work with a work to familiar objects visitors might know.

It's as big as a [car, a soccer ball, a fist].

The railing is waist high.

The body of the teapot has the shape of a pear standing on its end.

The bell tower's three sections look like three square boxes piled one atop another.

Then Give the Big Picture -- Don't Start with a Detail

It’s best to then quickly offer the overall impression of a work that most viewers have, the content as well as style, if appropriate. You're going to start with the general and then move to the specifics To continue using Hopper’s painting as an example:

It shows a block of three attached buildings, all two stories tall, with shops on the street level and apartments above them. The buildings extend horizontally across the painting from the left edge to the right edge.

Sometimes it is possible to be a bit more intriguing in your summary.

For the painting at right by J. Alden Weir titled The Factory Village, I wrote this introduction:

The essence of what you see in the painting is a factory and a village.

But what dominates the painting is instead nature.

Establish a Point of View

For a representational painting, describe the point of view the artist has given the viewer, who is now your listener. Are we seated across a table from the subject or are we across a field? Are we looking down on or up at the subject? Again using the Hopper painting:

You see the buildings as if you’re standing across the street from them.

For the Weir painting above, you might write:

The view is from a hill looking down into a New England village from a distance.

But the view is partially obstructed by a large tree on your left in the foreground, close to you.

Also, when you use phrases like “to the left” or “on the right,” explain whether you’re referring to your point of view as viewer of the painting, or the point of view of the subject in the painting.

For describing sculpture, it’s equally important to establish a point of view for the listener. Where are you standing as you describe? Facing its front? Or side? Looking up at it from its base? Explain if you are describing one point of view, or if you will describe it from various points around it.

As the audio description continues, remember that you are incrementally building up an image in the mind of the listener. Each line should add to that image in an order and in sequence. And you should first tell the listener what that order will be.

I will describe the sculpture starting with the crown on his head, moving down to his feet.

The painting is primarily made up of three horizontal sections. I will begin with the upper third of the painting.

Then Bring on the Details -- in Some Order

Plan the best sequence for describing the details. Sometimes it's best to start at the bottom and move up. Or vice versa.

Or maybe begin with the most prominent feature and move from that. The key is to follow a certain order, and whatever you decide, tell your listeners the plan to help them prepare to build their mental image. For example:

The painting is primarily made up three horizontal sections. I will begin with the upper third of the painting.

I will describe the facade of the building by beginning at the ground floor and moving up to the roofline.

As your audio description continues, remember that you are building an image in the listener's mind.

Direct the Listener’s Pose

Sometimes you can suggest that a listener use his or her body to feel a certain shape, or to understand the pose of a figure in a painting or sculpture.

Along the top edge of the roof is a line of carved wooden shapes. The shape is kind of like a large leaf. Hold your hand out flat and spread your fingers wide and you’ll have an idea of the shape.

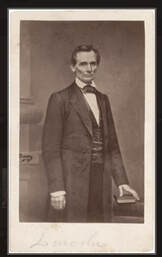

To understand Lincoln’s pose in Brady’s photograph try this. Stand up straight and imagine the camera is directly in front of you. Keep your head facing forward, while turning your shoulders to the right about 45 degrees. Your right hand hangs straight down; your left hand rests on a pile of books on a short wooden column.

The sculpture consists of the model’s head and face, a chignon or knot of hair at the back of her head, and her hands and forearms. To understand the pose, try this. Place your palms together in a prayer pose, and also try to put your forearms together so they touch. Now keeping your arms together, place your joined hands on the left side of our chin and tilt your head down a bit. That’s the sculpture.

Describe What You See -- Not What You Think or Feel

Be careful to use accurate and objective words so that you don't sway a blind listener's point of view. For an example, look at this painting of Philip IV by Velazquez.

You might say his his face looks sleepy, or bored, or peaceful. But you'd be editorializing. Instead you might say "He is not smiling" or "His expression is hard to read."

But if there are details in the painting that make you think he is sleepy or bored, then describe the details. Say what you see.

Resist the urge to share the emotional state you think is inferred. Instead, describe details which can lead the listener to his/her own opinion. What you tell them will help them answer the question, "What did the artist put in this work that leads me to a certain conclusion?"

Color

Don’t hesitate to include color in your audio descriptions. Often blind people had vision earlier in life and recall the world in color. Even congenitally blind know the cultural associations with various colors. And today there are smart phone apps that can tell a blind person what color something is.

Be careful to use accurate and objective words so that you don't sway a blind listener's point of view. For an example, look at this painting of Philip IV by Velazquez.

You might say his his face looks sleepy, or bored, or peaceful. But you'd be editorializing. Instead you might say "He is not smiling" or "His expression is hard to read."

But if there are details in the painting that make you think he is sleepy or bored, then describe the details. Say what you see.

Resist the urge to share the emotional state you think is inferred. Instead, describe details which can lead the listener to his/her own opinion. What you tell them will help them answer the question, "What did the artist put in this work that leads me to a certain conclusion?"

Color

Don’t hesitate to include color in your audio descriptions. Often blind people had vision earlier in life and recall the world in color. Even congenitally blind know the cultural associations with various colors. And today there are smart phone apps that can tell a blind person what color something is.

Refer to technique

When possible, make reference to the style and technique AND how that technique affects a viewer’s experience. For example, is the paint applied thickly and roughly or with a fine delicate line? Describe how the technique serves the artist’s creativity and the affect on the viewer. This type of information should reflect your research into the views of critics and the public.

Here’s an example I wrote in an audio description stop for a painting by Cezanne.

Cezanne was not interested in painting realistic views of his subjects. We can tell the hillside surrounding the mission is thick with nature. But he does not paint realistic trees. Instead he used small parallel brush strokes with many colors to build up the impression of a lush woodland. And in some places he has deliberately let the off-white canvas peek through, becoming an element of the landscape.

When possible, make reference to the style and technique AND how that technique affects a viewer’s experience. For example, is the paint applied thickly and roughly or with a fine delicate line? Describe how the technique serves the artist’s creativity and the affect on the viewer. This type of information should reflect your research into the views of critics and the public.

Here’s an example I wrote in an audio description stop for a painting by Cezanne.

Cezanne was not interested in painting realistic views of his subjects. We can tell the hillside surrounding the mission is thick with nature. But he does not paint realistic trees. Instead he used small parallel brush strokes with many colors to build up the impression of a lush woodland. And in some places he has deliberately let the off-white canvas peek through, becoming an element of the landscape.

Use Touch When You Can

If you have tactile diagrams to accompany the works you describe, by all means use them. Some museums use tactiles before or after listening to audio description; some museums have visitors touch while listening.

If you have access to artists in an exhibit, ask if they would provide a small tactile sample of their artwork for blind visitors to touch. Of course, the venue hosting the exhibit must be open to allowing such a possibility.

**********

If you have tactile diagrams to accompany the works you describe, by all means use them. Some museums use tactiles before or after listening to audio description; some museums have visitors touch while listening.

If you have access to artists in an exhibit, ask if they would provide a small tactile sample of their artwork for blind visitors to touch. Of course, the venue hosting the exhibit must be open to allowing such a possibility.

**********